Growing up too fast: The rise and fall of Teen culture

Teenagers have always been a little bit mythical , a strange in-between species, too old for the sandpit but too young for the bars, moving through the world in a haze of hormones, music, and unique fashion. For a long time, teenhood was this messy training ground for figuring out who you were going to be, the prelude to adulthood. Teen culture was distinct, specific, and profitable- from music to fashion, magazines to movies- it gave young people spaces to experiment, make mistakes and explore and form identities, relationships and communities. Today, that culture feels smaller and thinner - teen culture still exists somewhat, although it feels increasingly less ‘teen’. Young people are now bleeding into adulthood earlier than ever, no longer contained within age-specific cultural or physical spaces, they are constantly moving through adult worlds, whether they want to or not. The collapse of teen-oriented retail stores, television shows and films, leisure spaces, and the rise of social media and smartphone accessibility has meant that teens are now consuming, performing, and competing in adult spheres long before they are emotionally or socially ready. The boundaries that once separated childhood, teenhood, and adulthood are now porous, and the commercial and cultural scaffolding that once made adolescence a distinct stage has all but vanished.

But before we can understand why teenhood feels so different now, we need to ask: where did the teenager even come from? And how did their culture take shape in the first place? To answer that, we’re going to step back in time, tracing the origins of youth as a concept, the birth of the teenager, and the ‘golden decades’ when teen culture was loud, lucrative, and impossible to ignore.

So, here’s a somewhat detailed, somewhat brief history of the teenager - that 27k I owe in tuition fees should come in handy here.

Before the Teenager: How childhood was invented

Before we jump into the Teenager, we have to first introduce their younger sibling - the child. For, well the entire history of humanity, children had been treated as miniature adults, from the poorest farm and factory labourers, to aristocratic heirs married off at 13 years old. The idea of a childhood didn’t emerge until the 17th and 18th centuries, the ideas of philosophers like John Locke, whose 1693 treatise Some Thoughts Concerning Education revolutionised the way upper class families educated their children (this applied to boys only unfortunately , however it was the 17th century so such is expected) it served as a manual for parents, combining medical advice, ethical guidance, and insights into child nature. He redefined childhood as a rational, formative stage where children learn best through example, gentle correction, and the cultivation of health, curiosity, and virtue.

“I’ve always had a fancy that Learning might be made a play and recreation to children.” (Locke, 1898, p.129)

French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau was inspired by Locke’s work, Emile, also a treatise on education is accepted as the first developmental account of childhood, with Rousseau identifying 5 stages: Infancy; Childhood; Preadolescence; Adolescence; Adulthood. For Rousseau, man is born innocent, and it is the environment around him which corrupts him, thus he felt strongly that parents and educators should protect children from harmful influences, and support their growth through teaching, play, and nurturing which aligned with their respective stage of development (Rousseau, 1892).

As aforementioned however, such experiences were limited to the children of the wealthiest in society, and then were limited further by those parents who would even be interested in the ideas of liberal philosophers to guide the raising of their children. As we move into the mid-late 19th century however, the sentiment that childhood was a distinct and valuable stage of life begins to trickle down into common society. In Britain for instance, Children evolved from being tools of labour to symbols of love, and the family, from being producers of economic capital, to consumers of it. I could write an entire post on just this change, so I'll keep this part as brief as possible. In the Victorian age, children of the poorest families (which most of the population was) could expect to start working from age 5, in either agricultural work, or the far more dangerous urban factories. In the early mid 19th century, the child became a topic of public and political discourse, particularly in conversations about their welfare, education, and rights. These discussions led to legislative changes that began by progressively limiting child labour (working hours, safety regulations, etc.), then moved toward education-especially the introduction of free and compulsory education. All the while, the perilous work of campaigners such as Charles Dickens, along with charitable organisations like Barnardo’s, helped shift public opinion. Improvements in healthcare, rising life expectancy, and falling child mortality rates also played their part, culminating in what became known as the ‘Golden Age’ of the child from around the 1870s. Children’s literature began to flourish, such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894) which continue to capture little imaginations well over a century later. Children’s toys and games became lucrative status symbols for the wealthy (china dolls, rocking horses etc), however even children of the poorest families had their own versions, often home-made, like dolls fashioned from pegs and fabric , or small wooden toys like the ‘Cup and ball’ and spinning tops. Children’s clothing were no longer just miniature versions of adult garments, but designed to be charming, cute and adorable, turning the child into something to be proudly shown off to friends and neighbours.

All that being said, to turn to the teenager specifically, it was Rousseau who first ‘discovered’ the adolescent, that awkwardly placed individual, between 12 and 20 years old; he was well ahead of the curve however, as the adolescent- now the ‘Teenager’- wouldn’t develop as a distinct and recognised social group until nearly 200 years later. Today, we understand the teenage years to be some of a human being’s most formative ones- a period of identity formation, experimentation, relationship building, fun, freedom and of course,mistake making. G. Stanley Hall’s 1904 book Adolescence was the first work to suggest such a perspective, Hall took a psychological approach, describing the period as one of intense “storm and stress”, helping to solidify the notion of adolescence as a turbulent and distinct developmental phase (Demos & Demos, 1969, p.635).

The idea of adolescence

The earliest recorded usage of the term ‘Teenager’ (as a single word) in print was in 1941, in the Popular Science magazine (Cosgrove, 2013), and by the mid-late 1940s, it began to circulate more widely as a way to describe the rebellious, experimental youngsters who were too old to be children, yet still too young to be adults. The post-war world was the perfect place for the ‘first generation’ of teenagers: jobs were plentiful, and the money was good, money which, for the most part, would be wholly theirs to spend as they pleased. In July 1959, British social scientist Mark Abrams identified this “significant new economic group” of 13–25 year olds, noting that Britain’s 6.4 million young people enjoyed low unemployment and commanded nearly £900 million a year in disposable income. For the youngsters who had grown up during the war, the concept of disposable income and consumerism was foreign to them - so one can only imagine what happens when you give teenagers access to money, consumer goods, and social spaces they’ve never had before. To quote Macquarrie:

“ In the memorable words of Jean Paul Sartre we are condemned to be free. Freedom is a wonderful gift but it is a monstrous burden for anyone to bear, particularly a teenager, and more particularly a female teenager. It means making choices, and choosing is fearfully hard” (Macquarrie, 1968, p.18)

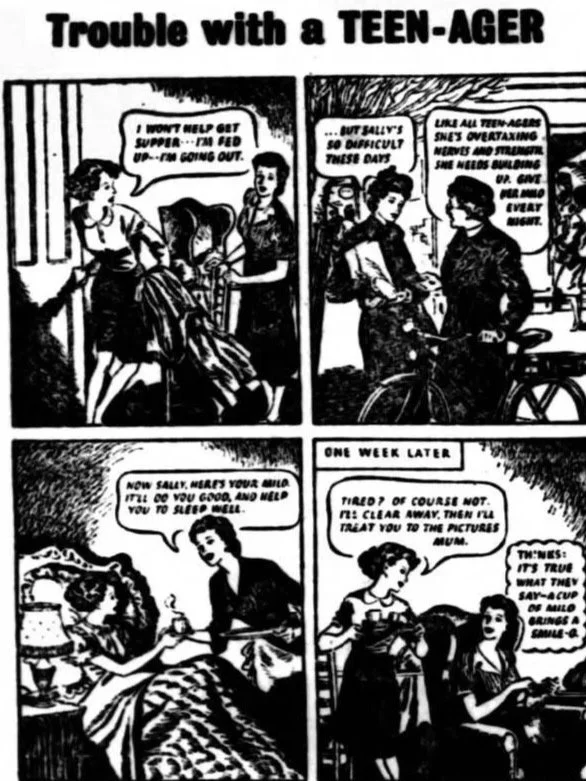

The term was exported to the UK around the same time, with some of the earliest references in the British Newspaper Archive centring on two key themes: fashion and delinquency. These two portrayals- the teenager as both a lucrative consumer and a social nuisance - would come to define how teenhood would be perceived in the west for decades to follow.

West London Observer, 3 March 1950

The ‘Golden Age’ of the teen

Post-war Britain and the birth of youth culture

The decades following WWII in the western world saw for the first time, the emergence of a distinctly recognisable youth culture, fuelled by economic prosperity, urban change, and much to the disdain of the older generations, the influence of American popular culture.

“To its critics, particularly among the older generations, this new consumerism often appeared vulgar, sensational and shallow. As Alwyn explains: “A sense that America has invented this concept of teenagers and now they're taking over here.”” (Bitesize, 2022)

In Britain, post war urban transformations were critical in the development of teenage culture, suburbanisation and the rise of motor vehicles redefined the use of streets and public spaces. Nathaus’ "All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go? Spaces and Conventions of Youth in 1950s Britain" explores this shift in great detail and provided the bulk of the knowledge for this section.Once multifunctional working class communal spaces, urban streets became subject to stricter regulations (in large part due to increased traffic thanks to the growing accessibility of cars), and as adults and children vacated them, teens entered (Nathaus, p. 46). At the same time, this pattern replicated itself in entertainment venues and social spaces such as variety theatres, cinemas, and dance halls .These once primarily working class adult spaces became inhabited by young people, who used them for socialising, experimentation and identity formation - away from the prying eyes of their parents.

Idols, magazines and fangirl community

At a time before mobile phones and entertainment technology, film/television, music, magazines, and fashion were the primary sources of teenage culture and identity. Variety theatres for instance had experienced a rapid decline post-war, with London’s 20 variety houses in 1950 sinking to a mere 4 by 1960 (Nathaus, p.47). One way these theatres realised they could survive was by courting younger audiences, booking American “modern rhythm singers”, (including household names such as Judy Garland, Nat King Cole and Frankie Laine) and eventually domestic acts such as Tommy Steele, who is regarded as Britain's first teen idol and rock and roll star (Nathaus, p.48-49). These performers attracted teenage girl fans, who reacted with unbridled enthusiasm to the appropriately dubbed “swoon singers”, newspapers painting a vivid picture of teenage girls gripped by “restless ecstasy” and “electric thrills,” clinging to one another amidst their squeals (Nathaus, p.65). Cinemas employed similar tactics, relying on youth amidst their declining attendance figures. The 1956 release of Rock Around the Clock marked a turning point with a wave of “teenpic” films that targeted youth through themes of rebellion, surf culture, and rock ’n’ roll, and films and music that were produced in the United States with a teenage audience in mind were distributed in Britain (Nathaus, p.50)

Hand in hand with magazines (which we’ll explore a little later), variety theatres and the film and television industries birthed the teen idol and what would come to be known as fangirl culture. In the 1950s, these international heartthrobs included James Dean , Elvis Presley and Frankie Avalon. As the British film and music industries developed further in the late 1950s and 60s, home grown ‘Dreamboats’ such as Sean Connery, Billy Fury, Cliff Richard, and of course, The Beatles, joined them. The 50s and 60s saw the birth of the Pop Star and the Film Star, and the recognition that the teen girls who idolised them were lucrative and enthusiastic consumers, who would buy almost any and everything attached to the face of their favourite star. Consumerism aside however, these infatuations also provided the basis for a lot of female friendships , teen girls could collectively swoon over last night’s Top of the Pops performances, and the exclusive interviews in the latest edition of their favourite magazines. Fangirling created community from common interests and has continued to be a part (albeit in slightly different ways) of female teen culture today- think everything from One Direction to Kpop to Taylor Swift.

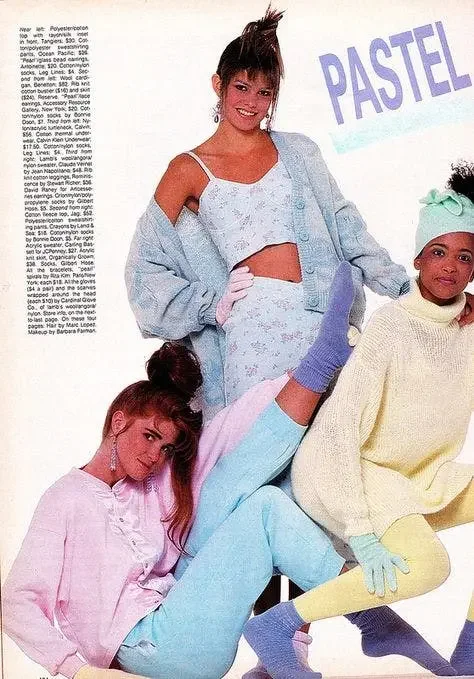

Fashion and the ‘youthquake’

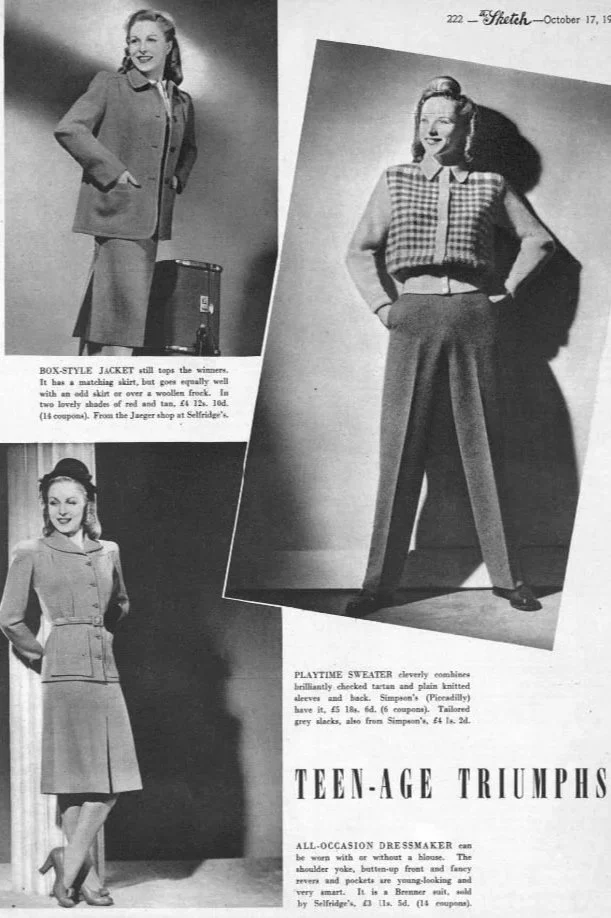

Moving our attention to fashion, clothing and style was central to youth self-expression, providing markers that not only distinguished teens from children and adults alike, but also from other teenagers, as subcultures (e.g. Mods, Rockers) which guided fashion, social groups and lifestyles arose. In the 1940s and 50s, teenage fashions largely mirrored adult trends, leaning towards a stylised ultra-femininity and formality: full skirts and petticoats with fitted tops and cinched waists as per Christian Dior’s “New Look” of 1947. But then, in the 1960s, this adult-like conservative aesthetic was disrupted by more radical, youth oriented styles, led by designers such as Mary Quant.

Quant was the most iconic fashion designer of the decade, she was the swinging sixties (again, I could write an entire piece on her impact on fashion alone, so I'll keep this dedication short). Her pieces were “strikingly modern in their simplicity” (V&A, 2019), with shorter hemlines, straighter, boxier silhouettes that were more androgynous than the ultra-feminine styles of prior, and above all, practical. She popularised the mini skirt, trousers, and tights, revolutionising teen fashion and embodying what Vogue Editor in Chief Diana Vreeland called the “youthquake” of the 1960s; her designs offered young women and girls clothes suited to their new lifestyles, allowing them to dance, run, and live life- creating a sharp visual distinction between the clothes their mothers wore, and those they wore, because as they had discovered, there was a vibrant life between childhood and motherhood!

Style icons of the movement included Twiggy, Mia Farrow, and Edie Sedgwick, even as Hollywood stars like Audrey Hepburn and Natalie Wood retained their iconic status’.

Before we jump further into the century, we should stop to visit the iconic teen magazine. Seventeen was the first publication targeting teenage girls , launched in 1944, it still exists today, though it is now almost entirely digital with just a few special print issues per year. It initially emphasized civic duties and career aspirations for young women, however soon moved into the oh-so-recognisable teen magazine formula of fashion, romance, and celebrities . Seventeen’s popularity meant that it played a significant role in shaping the idea of a teenager as a distinct social and cultural identity, and soon, countless replicas appeared. British publications like Jackie (1964-1993), which was the UK’s best-selling teen magazine for ten years, and Smash Hits (1978-2006) which was a music (mostly pop) based periodical filled store and bedroom shelves alike. Into the 80s, Just Seventeen/J-17 (1983-2004) would take over as market leader, followed by Sugar in the mid 1990s. By the turn of the millennia, teen versions of all the major magazines- Teen Vogue (2003), CosmoGirl (1999-2009) and Elle Girl (2001-2006)- could be found, a testament to the profitability of the demographic. These magazines were guides to teenhood- advice columns for romantic troubles, celebrity gossip, fashion and beauty how-to’s and many would often include freebies like cosmetics, vouchers, or fold out posters of popular bands and film stars to fuel fangirl obsessions.

Film, Tv and the peak of teen pop culture

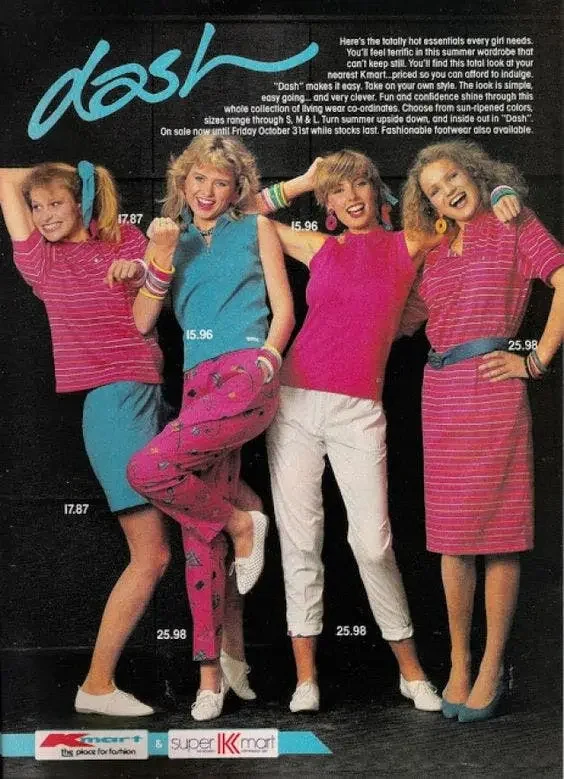

Skipping forward to the 1990s, the new digital world was beginning to take shape. The ’90s was the era of the teen coming of age film, preceded by ‘80s classics such as Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club, this decade saw icons such as Clueless, 10 Things I Hate About You, Never Been Kissed, Romeo and Juliet, and She’s All That, alongside teen thrillers like I Know What You Did Last Summer and Scream. On the small screen, sitcoms such as The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Moesha reflected Black American teen experiences and the recognition of more diverse, intersectional stories, while Boy Meets World, Dawson’s Creek, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Sabrina the Teenage Witch, all catering to different parts of the teen demographic, from preteen to high schooler. Subcultural style flourished (Grunge, Hip-Hop etc) but mainstream teen fashion saw darker tones replacing neon brights, and an emphasis on more comfortable, often unisex designs- baggy jeans, graphic band tees, windbreakers, and sneakers.

By the 2000s and early 2010s, the sheer volume of teen media content had reached new heights. We saw the emergence of the short lived “tween” demographic (9- 12). For them, Disney musicals (High School Musical, Camp Rock) and sitcoms (Lizzie McGuire, That’s So Raven, The Suite Life of Zack & Cody, Victorious) dominated after-school viewing. Meanwhile, older teens saw a mix of lighthearted comedies (Mean Girls, She’s the Man, John Tucker Must Die) and edgier dramas (Skins, Twilight, Pretty Little Liars, Teen Wolf), reflecting a cultural appetite for grittier dramas and fantasy escapism (thank the 2008 recession for that) . Fashion mirrored this shift, early 2000s style was bright, playful, and heavy on accessories - stores such as Victoria’s Secret PINK, Jane Norman, Justice and Claire’s targeted the youth specifically- evolving by the late decade into skinny jeans, metallic accents, studs, and the darker, moodier palettes of on screen trendsetters. Scene , emo, and hipster subcultures also exploded, propelled by online platforms such as MySpace and Tumblr, which became hubs of teen culture and socialisation.

Today’s Teenhood

So, now that we’ve explored the past, let’s resituate ourselves into the present day- the teenager is still here, in name, but the experiences and culture of the teenager feels thinner than ever. From the 1950s, teenhood was its own distinct cultural and developmental stage, with its own music, films, clothes, and rituals. Yes, it was immensely profitable, but it was also culturally nourishing. With the erosion of third spaces and the collapse of teen specific consumer markets, young people are increasingly bleeding into adult worlds- adult online spaces, adult social settings, adult consumer categories - without the protective buffer of a stage that used to belong to them only. It was a place where you could make bad choices and switch identities out like clothes on a doll, discarding them without consequence. The tweens and teens of today however don’t have that luxury. I don’t mean to suggest that anybody who chose to express themselves (especially those who expressed difference) in previous generations met no difficulty, teens are some of the most judgmental and mean people, and that fact likely hasn’t changed much, but what has changed is the medium through which they express this judgment. Social media is a huge part of young people’s lives and it has rewritten what it means to be a teen. Bad makeup or style phases are no longer just a local embarrassment to outgrow, everything can be photographed, screenshotted and stored, so teens perform for a permanent audience of friends, peers, and strangers. That constant visibility breeds self surveillance while algorithms amplify gossip and humiliation faster than any playground whisper ever could. Tiktok may push a random video from that one ‘weird kid’ into multimillion view virality, one look at the comments and that kid is being ripped to shreds by not only his peers, but by adults too - this isn’t something that can be lived down so easily, because social media never forgets.

The loss of third spaces

In 1989, Sociologist Ray Oldenburg introduced the concept of “third places”, which he defined as “the core settings of informal public life”.

“The third place is a generic designation for a great variety of public places that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work.” (Oldenburg, 1989)

These places could be barber shops, parks, cafes, gyms, libraries etc - often places centered around a common interest that allow for carefree socialisation, connection and community outside of the home (the “first place”) and the workplace (the “second place”). Oldenburg emphasised that balance and happiness in life are achieved through frequent interaction with all 3 places. Third places function the same for children and teens, allowing for communal connection outside of the home, and in their case, school. They would almost always be child-oriented, spaces designed for children specifically, separate to adults. In previous decades, third spaces were not only more common, but also more accessible, affordable and safe; teenagers could lay claim to a variety of youth-oriented third spaces- local authority or church funded youth clubs, arcades, roller/ice rinks, malls, parks, and extracurriculars. These spaces acted as neutral grounds where young people could negotiate social hierarchies, learn interpersonal skills, and develop autonomy outside both the home and school; and were incubators for identity formation, community and subculture. However youth oriented third spaces have been in steady decline since the mid-late 2000s. Community centres and public youth services have been subject to major funding cuts; extracurriculars and clubs have become more and more expensive and increasingly far and few between; local parks aren’t maintained and therefore often inhabited by delinquents or used for drug deals; and cinemas, arcades and rinks are not only more expensive, but also becoming rarities (exacerbated even more so by the COVID-19 pandemic) (Alao, 2024); Malls, where teens once wandered from Claire’s to HMV to the food court, have lost their status as brick and mortar retail declines in the west, leaving many teen focused stores to close branches, move online, or disappear entirely. With fewer places to “be” in person, teens aren’t meeting up in the same way, and why would they?

The result is generations of young people whose third spaces are increasingly digital , and more often than not, increasingly adult.

Teen fashion and the collapse of the teen demographic

The teen as a distinct consumer group, barely exists anymore. When I was younger, shopping in Bhs, ASDA and M&S with my mum, I remember seeing clothes sized 13-14, or 14-15 in children’s sections, but by the time i reached that age, nobody I knew, myself included, was wearing those clothes- as they had already graduated to the women’s and men’s section. On non-uniform days or trips to the town centre on weekends, no one was wearing the tween and teen clothes that had filled store racks years before, instead we scrolled PrettyLittleThing, Boohoo and H&M, buying clothes cut for women in their twenties, following trends set by, well, other women in their twenties. The few teen and tween targeted brands left have either thinned into irrelevance or aged their marketing up to court older buyers. The only age ranges that still have a robust dedicated retail market are babies, toddlers and kids below 10, because no one’s trying to make them look 25 (though in saying that, there has been a lot of criticism recently on the inappropriateness of clothes for toddlers and young children) (Burke, 2022) (Heisey, 2014).

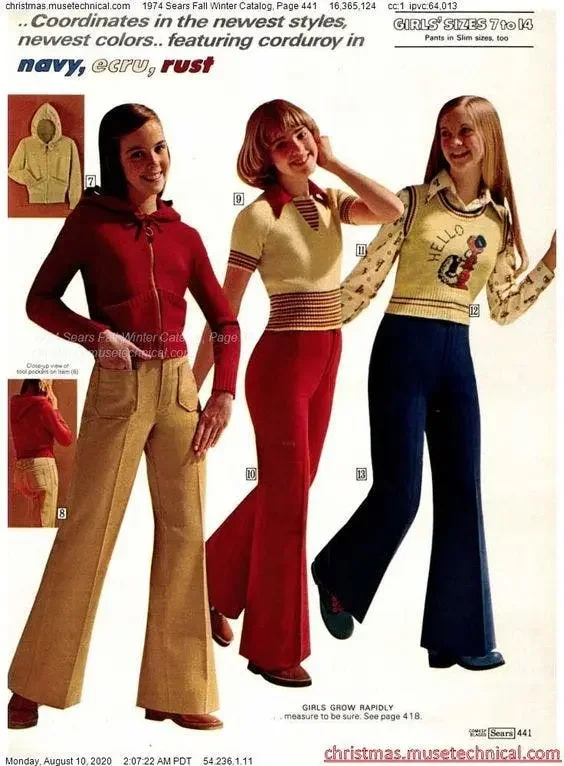

In previous decades, kid and teen fashion has mirrored mainstream adult styles, e.g. flared jeans and blouses from the 1970s, boxy denim and oversized sweaters of the 80s, but the key difference was that these styles were suitable to move across age lines, and so a teen girl could dress like her older sister, without being prematurely sexualised.Today, the problem is that mainstream trends, especially since the mid-2010s, have tilted heavily towards hyper provocative and sexualised silhouettes. Ultra-short hemlines, cut outs, slits, bodycon everything- fuelled and normalised by the triple threat of fast fashion, celebrity and influencer culture, and social media. So, as the dominant aesthetics for women become shorter, tighter, sheerer and more revealing, and these fill up stores, even though they aren’t marketed or designed for teens specifically, they become what teens purchase. The result is that teens don’t just look older; they’re dressed as if they are older, and they feel older because those lines between child—>tween—>teen—>adult are eroding more and more each year.

Images credit of Hannah Amini, "Teen Fashion Trends by the Decade", 2022.

The Sketch, 17 October 1945

’Sephora kids’ , makeup and beauty surveillance

Crucial to the ‘looking older' phenomenon is makeup, specifically how now, girls barely into their mid-teens (and younger) now step out in full faces of perfectly applied makeup. Now, this isn’t necessarily a recent development, I remember seeing 16 and 17 year old girls with heavy makeup as a kid and by the time I reached high school age, the story was the same. However, it's no longer just those older teens, over the years the age of the girls sporting such makeup has lowered , and crucially, it’s no longer bad makeup. The awkward, experimental “bad makeup” phase that was once a rite of passage has disappeared, so too have teen specific makeup trends and products that once distinguished the 15 year olds from the 21 year olds. The days of searching ‘High/Middle school makeup tutorial’ and being greeted by baby lips lip balms and the great lash mascara are far gone ; now tweens and teens are going onto tiktok and following the same tutorials as twenty somethings, and using, or begging their parents for, the same products.

This development is part of a wider shift- the concentration of hyper-consumerist content on social media, and the seepage of this content, along with increasingly unattainable beauty standards, into young people’s lives. They watch the same videos, from the same content creators, from the same platforms because teen dominated social media platforms (e.g MySpace) , and teen content creators (e.g. Bethany Mota, MyLifeasEva, Zoella etc.) closed down, or grew up respectively, and were never replaced. While the panic was centered around younger girls, aged between 9-11 roughly, the ‘Sephora Kids’ hysteria in 2024 shows just how far this content and ultra-consumerist beauty ideals are seeping. In an article from Vogue Business earlier this year, Sara Radin said this :

“They’re called the ‘Sephora kids’, and you might’ve seen a gaggle of them out shopping on your recent trip to the cosmetics store. These tweens, mostly equipped with their parents’ cash, love adult brands and products, from $90 Drunk Elephant serums and $30 Rare Beauty blushes to Sol de Janeiro body mists and Laneige lip masks in every colour of the rainbow.

It’s a scene borne from social media consumption — hours of YouTube and TikTok tutorials and brand advertisements — that tends to ruffle the feathers of older shoppers.”

She also highlights how those in the tween and early teen categories have become big consumers in the beauty market, consumption which is projected to reach $5.5 trillion by 2029. Skincare is one of their biggest fascinations, which is deeply concerning- some of these children seem hellbent on owning aging preventative retinol creams, and following 7 step skincare routines with mid-high end products that I, at 20, still hesitate to splurge on. Consumer intelligence data has found that Gen-Alpha has spent $17.9m on Byoma Skincare, $41.7m on Bubble Skincare and $63.4m on Drunk Elephant (Radin, 2025) and these numbers will only continue to balloon.

The death of the subculture, and rise of the aesthetic

Just as with the death of the “phase” , subcultures have also almost entirely ceased to exist. Once you could be a mod, a rocker, a hippie, a punk or an emo- even the so called ‘nerds’, exaggerated teen films aside, bonded over gaming, sci-fi, and tabletop games to create their own communities. The APA defines a ‘subculture’ as “a group that maintains a characteristic set of customs, behaviors, interests, or beliefs that serves to distinguish it from the larger culture in which the members live” . Today, subcultures have declined in prominence, and been replaced with hollowed out ‘aesthetics’- neat little boxes like “downtown girl”, “blokecore”, “cottagecore” and “coquette” that you can find all over tiktok and instagram- curated identities based purely on visuals like clothing, makeup, and sometimes decor and homeware. These “__core” identities are surface level and superficial, assembled from pinterest boards and tiktok videos, and are a far cry from the subcultures that preceded them. They rarely exist in physical spaces, meaning there's no genuine community and social fabric to sustain them; You can be “balletcore” online, but you probably aren’t meeting other balletcore girls at the park on Saturday. It’s all transient, like a digital costume change. These aesthetics also bypass lifestyle , values and beliefs, and are often extremely rigid and self restrictive - “this doesn’t fit my aesthetic so I won’t wear it” - further emphasising how they aren’t about genuine self expression.

Media and the shrinking teen world

Teen media has also followed the same trajectory, the once stacked shelves of teen magazines have shrunk to almost nothing, the few left standing existing as digital issues which, let’s be honest, no teens are reading. Television, once a time-bound shared part of teen culture (waiting to discuss last night’s episode of your favourite show with your friends) , has now made way for streaming with its individualised ‘watch anytime’ viewing. MTV’s fall from grace embodies this. In its prime, it was the beating heart of teen pop culture with music videos, chart shows, celebrity gossip, dating shows, and ridiculous reality series. But in the early 2010s, the channel pivoted away from music entirely, filling airtime with reality shows and reruns. Teen music award shows like the KCAs and The VMAs, once a true cultural event that could make or break an artist’s image overnight, now limp along as a shadow of their former selves. Without these shared pop culture touchpoints, teen life has grown more fragmented, more individualised.

Additionally, many shows are no longer geared purely towards teens, as in order to cater to as wide an audience as possible (adults), shows have become hyper mature in terms of themes - think euphoria. The same pattern follows with films, the rom-com has died (Angus, 2024) (Finnan, 2023) , and so too has the coming of age film, as movie studios are rejecting the kind of mid budget films that made the 2000s in favour of huge million dollar budget blockbusters. Cinema closures have also exacerbated this issue- once a popular teen hangout, the cinema is now either closed, too expensive, or not showing anything that appeals to young people. Teens today are therefore gravitating towards adult film and tv, because there’s simply not much around for them , and streaming services make it so they can access age inappropriate shows at the touch of a finger.

Teen idols and music stars have also become redundant. In the past, young audiences had their own music idols- boybands, girlbands and pop stars whose images and lyrics were curated for younger fans (with the stars often young themselves). The last I can think of are Justin Bieber, One Direction and Little Mix, there's been a few groups and soloists here and there since but no one has touched that level of stardom and fan culture since. Today, Kpop groups are the only artists that come to mind that produce music, choreography and visuals with young audiences in mind, and achieve the kind of cult-like fandom following synonymous with the teen idol. Teens today simply gravitate towards the mainstream artists of whatever genre they are interested in, and listen to the exact same music as adults. Much of the most popular music today contains adult themes, explicit lyrics and even more explicit music videos. Of course, music like this isn’t a new invention, but now, it is mainstream, rather than being limited to particular subcultures, and is easily accessible- no need to purchase a CD now because all you have to do is open an app. This ease of access means children can- and do - engage with songs and videos far beyond their intended age range -see the recent controversy around artist Sexyy Redd’s songs being recited by kids as young as 4 - and when this starts so young, it can desensitise teens to and glorify behaviours which are inappropriate, dangerous and even criminal.

Final thoughts

We don’t need a funeral for the teenager, we need a new blueprint. Teenhood hasn’t vanished because of fate, it’s been dismantled by the choices of adults: austerity policies that have gutted funding for anything youth related, retail strategies prioritising the more profitable adult market and social platform designs that aren’t effectively protecting the youth from the adult world.

If we want adolescents to have the messy, private (and age appropriate!) rehearsal spaces they used to have, we have to build it back for them deliberately. Fund youth services and extracurriculars, Protect parks, libraries, cinemas and affordable community spaces as places kids can actually be together. Push media makers to make content that speaks to teens and for social platform features that offer stronger privacy for minors, and limits on algorithmic amplification of humiliation.

Teenagers will always make their own culture, but they create it from the world and resources we give them.Strip away their own spaces, their own styles, their own media, and it’s no wonder they end up borrowing ours- when they start appearing in our spaces, in our clothes, listening to our music, watching our tv shows etc- not because they want to skip teenhood, but because there’s no alternative for them.

Have any thoughts? Contact me

email: jaz040504@gmail.com

Sources

Amini, Hannah. “Teen Fashion Trends by the Decade”. L’Officiel. July 24, 2022. https://www.lofficielusa.com/fashion/teen-fashion-trends-decades-90s-y2k-tiktok

Angus, Haaniyah. “Is the romcom dead”. Dazed. February 14, 2024. https://www.dazeddigital.com/film-tv/article/61943/1/is-the-romcom-dead-anyone-but-you-sydney-sweeney

BBC Bitesize. “Who were the first teenagers?”. Accessed July 30, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zqbf3j6

Burke, Trine Jensen. “Crop Tops And Sexy Slogans: Why Are Kids Clothes Getting So Adult?”. Everymum. Accessed August 6 2025. https://everymum.ie/kids/crop-tops-and-sexy-slogans-why-are-kids-clothes-getting-so-adult/

Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture”. Time, September 28, 2013. https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/

Demos, John, and Virginia Demos. “Adolescence in Historical Perspective.” Journal of Marriage and Family 31, no. 4 (1969): 632–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/349302.

Finnan, Sarah. “Death of the rom-com or rom-com renaissance? Julia Roberts has a one-way ticket to paradise”. Image. February 24, 2023. https://www.image.ie/living/death-of-the-rom-com-or-rom-com-renaissance-julia-roberts-has-a-one-way-ticket-to-paradise-593500

Heisey, Monica. “It freaks me out when kids dress like tiny, hip adults”. Fashion. May 27, 2014. https://fashionmagazine.com/style/it-freaks-me-out-when-kids-dress-like-tiny-hip-adults/

Locke, John. Some Thoughts Concerning Education. United Kingdom: University Press, 1898.

Macquarrie, J. W. "THE TEENAGER: A BY-PRODUCT OF INDUSTRIALISM." Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory (1968): 15-25.

Nathaus, Klaus. " All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go? Spaces and Conventions of Youth in 1950s Britain." Geschichte und Gesellschaft 41, no. 1 (2015): 40-70.

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts and how they get you through the day. New York: Paragon House, 1989.

Radin, Sarah. “The ‘Sephora kids’ aren’t going anywhere”. Vogue Business. January 28, 2025. https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/beauty/the-sephora-kids-arent-going-anywhere

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Émile: Or, Treatise on Education. United States: D. Appleton, 1892.

Staveley-Wadham, Rose. “What Should a Teenager Be? Exploring the Birth of the Teenager in British Newspaper Archive”. British Newspaper Archive. March 30, 2020. https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2020/03/30/birth-of-the-teenager/

V&A. “Introducing Mary Quant”. Accessed August 3, 2025.